A few of the 150 photos and drawings found in the book.

East Texas: Neches River, July 1924. Conservationists and honest folk stood in favor of game warden enforcement efforts but a few outlaws threatened to retaliate against the officers. The wardens maintained a constant guard when removing illegal fish traps and hoop nets. Game Wardens (left to right) Ira Lewis, Darty Turner, Herbert Ward and Sam Turner burn a crude fish trap made of wood.

Near Encinal, North Central Webb County, December 1985. Game Wardens responded to the complaint of a Southwest Texas landowner, whose two ranches amounted to more than 134 square miles of pastureland. Although some of the ranch roads were washed out or overgrown, the pastures’ thickets afforded prime hiding places for trespassers afoot to bag trophy bucks in areas difficult to access by motor vehicles.

At the ranch headquarters, the owner had recently mowed down the thorny brush in a small pasture known locally as a “trap.” Here Texas Game Wardens convene at the trap. (Left to right): James Oden, Steve Backor, Jim Mangum, Rep Moore, Fred Burns (standing) and Mike Bradshaw. Burns is a Deputy Game Warden who serves the state without pay.

The book’s drawing of a Texas diamondback rattlesnake was the work of high school student Holli Fowler, in 2005.

West Texas, circa 1948. Game Warden Bob Evins and his trusty dog Pluto admire a recently deceased bobcat. As sole warden assigned to the counties of Crane, Glasscock, Reagan, Upton, Ector and Midland, Evins’s patrols lasted several days at a time.

Texas-Mexican border: Northwestern Webb County, 1977. As a pair of roadhunters drove along the unpaved Mines Road, (a.k.a. “Military Road”) they shot this white-tailed buck as it roamed a private ranch pasture. Afraid to retrieve their trophy buck or its rack of antlers, the lawbreakers tethered the deer to prevent scavenging animals from devouring the soft tissue and dragging away the buck's head. In a job smacking of amateurism, the poachers apparently planned to leave the carcass for several days so feral hogs, buzzards and maggots would be strip away the flesh and clean the bones. The poachers could return later and saw the antlers from the skull. Over a period of nine days, several game wardens took turns on watch, awaiting the culprits. When “Marcel Bento” and “Klemont Suggs” returned to retrieve the antlers, Game Warden Lt. John Caudle arrested them.

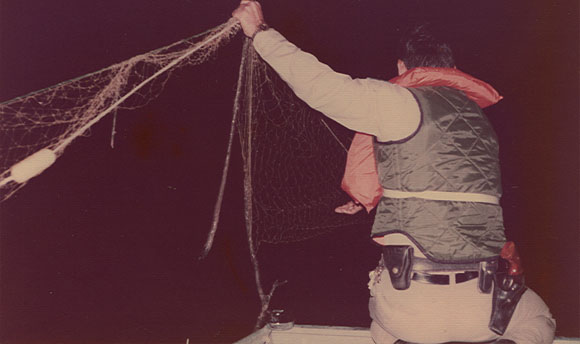

Texas-Mexico border: Rio Grande River a few miles upstream from Falcon Lake, 1976. Many Mexican fishermen trespass into Texas waters to ensconce their illegal gill nets. Game wardens remove nets totaling untold thousands of feet and dozens of fish traps each year. Here, during a nocturnal raid south of San Ygnacio, Texas Game Warden Eliseo Padilla takes his turn at the dirty job of pulling nets.

South Texas Brush Country, circa 1989: Poachers often lie awake at night plotting how they might slip into a large ranch to kill a huge trophy whitetail buck. Some outlaws clandestinely tote backpacks laden with supplies into ranches for extended poaching trips. The stealthy hunters camp for days at a time, avoid lighting fires and—unless cooking with heat derived from flameless fuel—eat cold grub.

Many veteran backpackers preferred a lightweight rifle in a .22 caliber. When the hunter steadies his crosshairs on a buck he attempts to kill the animal cleanly with one bullet. “It’s harder for a game warden to figure out where a singe shot comes from,” says one poacher.

When in the daylight stealth mode, the poachers stick to the shadows and cover their bodies with camouflage clothing that includes gloves and head net or face paint. Going so far as to cover their rifles with dull paint or strips of camouflage cloth, the lawbreakers strive to mask all reflective surfaces.

Photo on the right shows a pair of burlap shoes designed to slip over a hunting boot. Other than leaving trail in the grass, when he wraps his boots, a sack-footed outlaw leaves hardly a trace of a footprint, even in bare soil.

The photo on the left shows an outlaw’s partner in crime resting at an old corral of cedar posts and mesquite limbs. Note the gear stacked behind the poacher and buck’s antlers hanging from his neck. These are “rattling horns” to call bucks. The antlers affixed to the posts were sawed from a deer’s head. Crooks often take only the antlers and leave the venison to rot.

Brewster County in West Texas, late 1930s. Ray Williams’ dark complexion, facial structure and high cheekbones caused a few people speculate he might be American Indian. To this, Ray was apt to reply, “I’m half javelina and half son-of-a-bitch. Which half you want?”

East Texas, 1984: Down filled vest belonging to Texas Game Warden Bobby Colston. When an illegal night hunter fired his .270 rifle at Colston, the projectile damaged the warden’s uniform in several places but left the warden with only a scratch. For demonstration purposes, the collar is exposed and doesn’t line up exactly as it did on the night the hunter mistook Colston for a deer. Note the paper circles over the bullet holes where the slug entered on Colston’s left side and poked a hole through the tip of the left shirt collar before passing between the necktie and shirt, cutting the backside of the tie. On its path, the bullet perforated the right collar and plowed a furrow near the right front of the vest.

This monument of a Texas Game Warden stands at the Freshwater Fisheries Center in Athens. The figure is affixed to a granite base and stands 13 feet high.